Am I a Luddite for worrying about AI chatbots taking my job? Maybe, but only because Luddites were awesome.

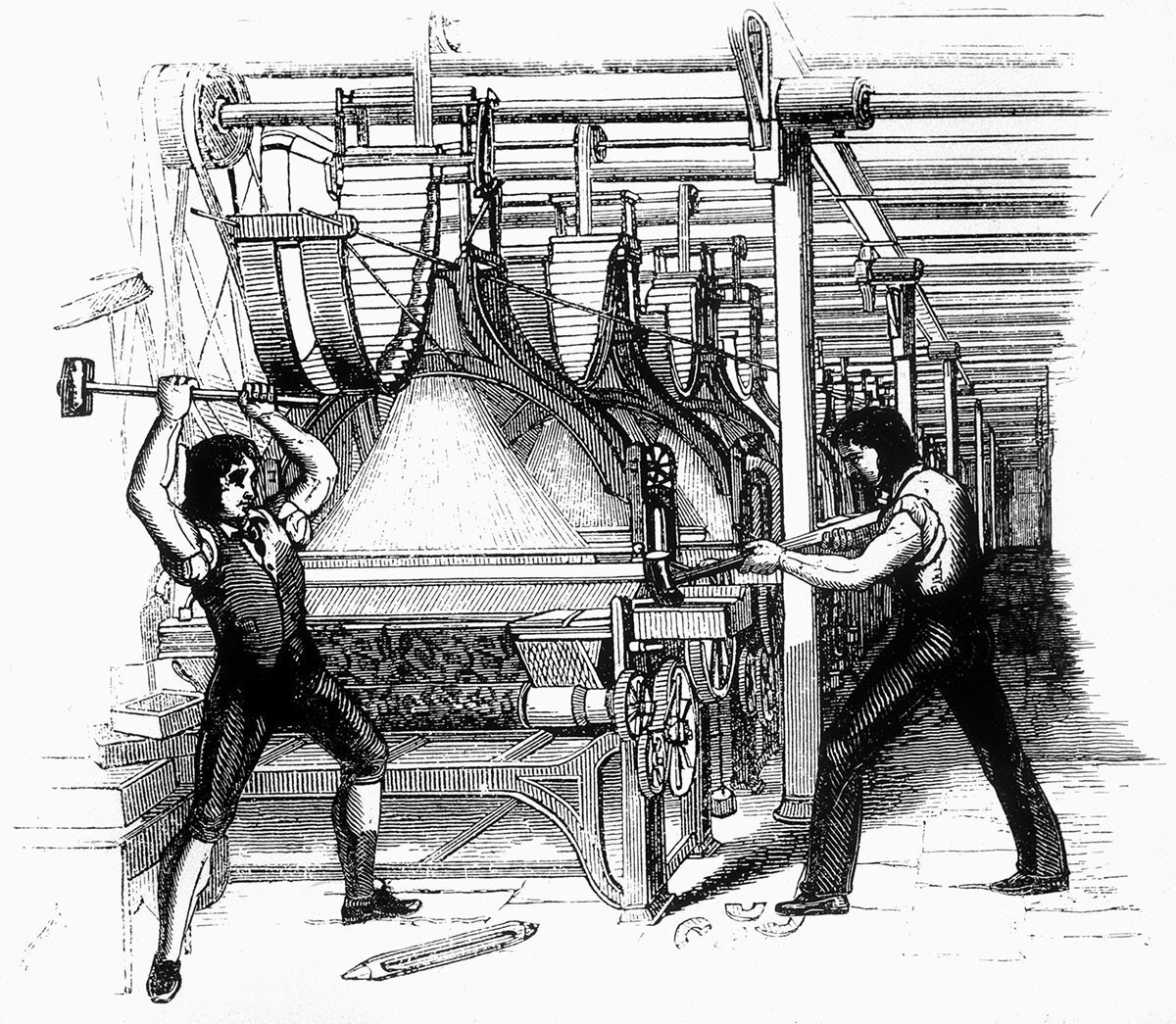

Early 19th-century engraving depicting frame-breaking. Wikimedia

A few weeks ago, leaders at some high-powered journalism outfits issued statements on how they’d use “generative artificial intelligence” in their publications. They were mostly talking about chatbots such as ChatGPT, automated systems that digest vast amounts of data — the entire internet, basically — and use high-powered language-model software to produce uncannily human-sounding text.

As those journalism bosses took notice, so too did those of us toiling in the journalism mines. I thought digesting vast amounts of information and outputting uncannily human-sounding copy was a job for me, a totally human person! Nick Thompson, the president of The Atlantic and my former boss, and Gideon Lichfield, the editor-in-chief of Wired and another former boss of mine, both told their teams to experiment joyfully, but cautiously.

AI chatbots have tended to invent untrue “facts” and spread the most vile biases, which is basically the opposite of my job. My current boss, Nich Carlson, wrote much the same thing. He wrote that AI should be a “bicycle of the mind,” and while none of us at Insider are allowed to write or edit articles using a chatbot, Carlson wrote, we should look for ways to use the things as adjuncts to our research and reporting, as well as to “solve writing problems.”

It’s hard not to see the faintly-chatbottish writing on the wall

Technological advancement is what makes America great, and what will usher in a utopian future of space stations, multicolored togas, Lucite sandals, and pills for food, right? Maybe the wheels of technological progress always leave tread marks on people who used to do what only humans could do. And if you’re opposed to that? What are you, some kind of Luddite?

I don’t want to be replaced by a machine, of course. But that’s not because of some Bolshevik anti-technological reflex. World-changing technology can be great — even the kind that can do (some of) my job. But I am here to defend the Luddites. Because despite what you may have heard (or may vaguely recall), they were not about destroying technology that would replace them. This fleeting early 19th-century movement wasn’t about technophobia. But it was, at least a little bit, about labor unions.

Of socks and steam

Now, I don’t want to say that reporters are freaking the hell out about the idea that chatbots can do our jobs, but we’re not not freaking out. People who write technical and marketing content are already getting the big chat-off, according to The Washington Post. Now, reporters’ work is quite a bit different than technical writing or mar-comm… but then, I would say that, wouldn’t I?

Just to be clear, my colleagues and I are on strike, but not over the possibility that Terminators will replace us. The Insider Union is fighting an illegal change management made to our healthcare while we were in ongoing negotiations for a contract. But Insider also just tried to lay off dozens of my colleagues, and publishes at a high volume most of the time. I can imagine how managers might see AI as a tool to make Insider cheaper and more efficient, in the language of business.

To make the connection to the Luddites, though, we first have to talk about underwear.

In her book “The Fabric of Civilization,” Virginia Postrel makes a convincing case that textiles — cloth, knitted and woven — were one of the first civilization-making technologies. The first wheel might well have been the spindle used to spin fibers like cotton, wool, or silk into thread. Weaving, which is nearly 10,000 years old, used the first binary mathematical system — exactly why it was so amenable to control by punch cards in Jacquard looms, a forerunner of modern digital computing.

Like baking, brewing, metallurgy, and ceramics, the textile work of spinning, knitting, and weaving was initially the province of women working in homes. It was an “art” or a “craft.” It only got to be a “technology” when men started doing it in factories at scale. Weird, huh?

The Industrial Revolution got into gear, as it were, in the 1700s, when people figured out how to apply steam power to all sorts of human labor — especially knitting and weaving. In that moment, just like this one, it was clear that a new technology was about to change everything. The question was if it would improve lives or just make a few people very wealthy.

The earliest knitting machines and looms needed thread, which meant a race to mechanize spinning. That happened, and what had been a home-based business went big time with the invention of patent machines — putting all those spinners, mostly women and kids, out of work. As Postrel wrote, “these ‘patent machines’ sparked an anti-technology backlash.

Protesters smashed machinery and demanded government relief.” In 1779, one of those protesters — this story is probably apocryphal, but whatever — was Ned Ludd, who smashed machines after having been whipped for not having a job, or maybe was a “dim-witted” apprentice weaver who, when told to “adjust” his loom, took a hammer to it. It’s not exactly John Henry versus the steam engine, but we’ll take what we can get.

Jacquard loom from 1810. Musee des Arts et Metiers, Paris. Adam Rogers

Either way, help did not come. The English government passed more and more laws favoring employers, laws making it illegal to beg or to be out of work, and laws against a minimum wage. Spinning got wholly mechanized, and mills eventually had more thread than they knew what to do with. So the Sauron-like eye of steam power turned to the looms that used it.

This is where the underwear comes in. Men were switching from knee-britches — sort of knee-length pant-type-things, worn with long ankle-to-knee coverings on each leg — to trousers, longer pants, with socks or hose. That increased demand not just for men’s knit socks, but for knit underwear — hosiery — for everyone. So in the first decades of the 1800s, the hosiery nexus in the East Midlands of England was hopping.

Typically, factories used a machine called a proper frame, which knitted thread into a tube, perfect for hosiery. A cheaper approach, though, was the wide frame, which knitted a flat piece of cloth that unskilled workers would cut and then sew into a tube shape with a seam — less durable than the tube, but easier and faster. It was a now-classic technological transition, from slow, high-quality, and rare, to fast, cheap, and widely available — but a bit crummier.

In 1811, the people who’d been making the stockings claimed that not only were these inferior goods that would threaten their profession, but that they had legal protection from such changes dating back to the 1600s. Nobody really bought that, so by February of 1812, they’d gone on enough nighttime “frame-breaking” raids to destroy 1,000 looms, and were calling themselves followers of Ned Ludd.

Meanwhile, in January of the same year, textile workers in woolen mills in Wiltshire were also facing the introduction of new machines: the gig mill and the shearing frame. The workers, calling themselves followers of General Ludd, took clubs, hammers, and guns to the shearing frames. Two months later, cotton handloom weavers in Lancashire did the same at powered-loom factories, calling themselves Luddites.

Here’s the thing: Lots of industries were dealing with the introduction of new, high-speed, labor-saving, efficient machines — sawmills and carpentry, printing, metalwork. It was a sort of revolution of industry, if you will. But as Adrian Randall pointed out in a 1998 article about Luddism, those other industries were better set up to metabolize the new machines into existing workflows. Small shops could bring in a machine and do more with the same people.

Textiles were different — small shops went away and factories replaced them. The Luddites “saw unregulated machinery as a major threat to the economic well-being of the community at large since it would displace workers, throwing them upon the scrap heap in exchange merely for the enhanced profit of the few,” Randall wrote. “They had no faith that the machine would enlarge markets.”

The Luddites didn’t frame-break indiscriminately. They focused on manufacturers “who doled out substandard wages or paid in goods rather than currency,” Richard Byrne wrote in The Baffler. “Within the same room, machines were smashed or spared according to the business practices of their owners.” Frame-breaking Luddites broke the new wide frames, and they became ideological heroes, the Robin Hoods of the day. And the Luddites didn’t expect a ban on all machines any more than anyone in 2023 expects companies to just turn off ChatGPT.

The Luddites did want regulation of their uses. Historians seem to agree that the Luddites didn’t want to destroy all technology, or even the technology that was doing something almost but not entirely unlike their jobs. They didn’t want a war. The Luddites didn’t want the products they made to suck, and they didn’t want to starve to death while machines made them.

Well, the Luddites got a war anyway. While they were trying to negotiate with factory owners at the end of 1811, the English government deployed thousands of soldiers to protect the mills and round up “the terrorists.” Frame-breaking continued over the ensuing decades; in 1830, English troops hanged or transported — banished — hundreds of people. But that rallied an incipient labor movement, so much so that by 1871, trade unions were made legal, leading to the rise of England’s Labour Party (and, indirectly, strikes including the Insider Union’s, 150 years later).

The warp and weft of labor

It seems unlikely that in 2023, the world’s writers are going to start smashing up server farms. But I’ve been a professional journalist for 30 years, and seeing chatbot pap get equated to what I do does somewhat vex me.

Some of publishers’ early forays into replacing … well, me, or people like me, have been disasters. Men’s Journal let a chatbot write an article and published it; it was riddled with errors. CNET ran chatbot-generated articles without telling anyone they were doing it; they both plagiarized and were, yes, also riddled with errors.

But I think most researchers and observers guess that chatbots will get better at being accurate — maybe not perfect, but then again, who is? Their makers might have to lose large piles of money and deploy underpaid human evaluators in lower-income countries to get them there, but it's a laudable goal. And if one of the main products of a chatbot is mid-but-acceptable prose recounting — if not building upon — available facts, well, gosh, what am I left with? An above-average ability to make puns?

The answer to that is an ability to report, an ability to find out things that aren’t already matters of public record (and therefore able to be incorporated into a training dataset), and the ability to do novel analyses. Chatbots are very good at figuring out statistical and vector relationships among words — the wide-frame knitting and power-loom weaving of the writing world. That’s why it makes sense to incorporate rules and guidelines for what role they’ll play in journalistic policies and, yes, contracts with journalism unions. The thread of Luddism got woven into the warp and weft of American organized labor; now it’s time to take a look at that overall design and see if more of the throughline should follow Ludd — not the destructive or violent parts, but the vehement belief that it’s worth fighting for work that’s meaningful, both in quality and compensation.

Business Outsider is a strike publication of Insider Union, which is a unit of The NewsGuild of New York.

Follow our Twitter for updates on the strike, and if you enjoyed this content and would like to throw in some cash for our members who are losing wages every day that we strike for a fair contract, feel free to visit our hardship fundraiser here. Want to help us tell the boss to reach a deal? Let Nich Carlson and Henry Blodget know you support us by sending a letter.